A recent visit to the Cowper and Newton Museum in the town of Olney has me thinking about the 18th-century equivalent of blogging, and the impoverishment of new technologies.

A recent visit to the Cowper and Newton Museum in the town of Olney has me thinking about the 18th-century equivalent of blogging, and the impoverishment of new technologies. Olney was on our list of out-of-the-way places to see, partly because we went on a John Newton kick a few years ago and read through Newton's 1793 Letters to a Wife by the Author of Cardiphonia, and then his more well-known 1764 volume, An Authentic Narrative of some Remarkable and Interesting Particulars in the Life of John Newton Communicated in a Series of Letters to the Reverend Mr. Haweis, Rector of Aldwinckle, Northamptonshire, and by him (at the Request of Friends) Now Made Public.

Olney was on our list of out-of-the-way places to see, partly because we went on a John Newton kick a few years ago and read through Newton's 1793 Letters to a Wife by the Author of Cardiphonia, and then his more well-known 1764 volume, An Authentic Narrative of some Remarkable and Interesting Particulars in the Life of John Newton Communicated in a Series of Letters to the Reverend Mr. Haweis, Rector of Aldwinckle, Northamptonshire, and by him (at the Request of Friends) Now Made Public. To these letter collections published during Newton's lifetime, we can add another one and a half volumes in Newton's collected works, as well as a few others compilations that did not make it into the collected works.

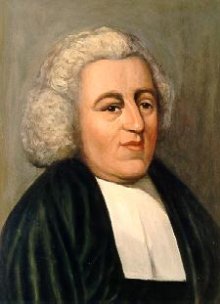

| Portrait of Cowper by William Blake in the Museum |

The museum is filled with Cowper memorabilia--his sofa, his chair, his personal wash-stand, his handkerchiefs, and replicas of his rabbits. This approach feels a bit dated now, more than a century after the museum opened, but it works well because Cowper was famous for writing about everyday life, and the personal artifacts are frequently matched with Cowper's own descriptions found in his poems and letters.

In the back of the garden behind the museum is Cowper's writing nook, which he described in letters as follows:

"I write in a nook that I call my Bouderie; it is a Summer House not much bigger than a Sedan chair, the door of which opens into the garden that is now crowded with pinks, roses and honeysuckles, and the window into my neighbour's orchard. ... It is secure from all noise, and a refuge from intrusion."

"As soon as breakfast is over, I retire to my nutshell of a Summer House which is my verse manufactory, and here I abide seldom less than three hours, and not often more. In the afternoon I return to it again, and all the daylight that follows, except what is devoted to a walk, is given to Homer."

The definitive edition of William Cowper's letters is the five-volume Oxford University Press edition of The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper.

You could say that Cowper and Newton wrote letters because they couldn't blog. Despite their personal address, letter writers often hoped for a wider audience. At least since Cicero, the publication of letter collections was an established practice, much like books that begin as blogs today. But the shift in technology has also led to a fundamental change in writing (and reading) practices. Now that communication is instant and potentially unlimited in scope, and the epistolary genre is all but obsolete, what have we lost?